Natalis Comes

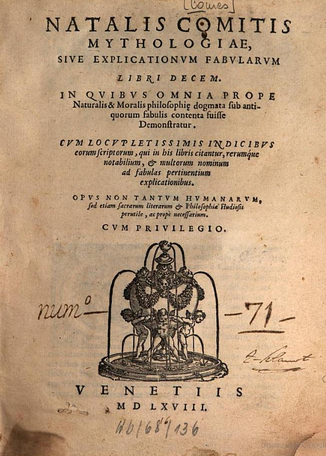

Natale Conti or Latin Natalis Comes, also Natalis de Comitibus and French Noël le Comte (15201582), was an Italian mythographer, poet, humanist and historian. His major work ''Mythologiae'', ten books written in Latin, was first published in Venice in 1567 and became a standard source for classical mythology in later Renaissance Europe. It was reprinted in numerous editions; after 1583, these were appended with a treatise on the Muses by Geoffroi Linocier. By the end of the 17th century, his name was virtually synonymous with mythology: a French dictionary in defining the term ''mythologie'' noted that it was the subject written about by Natalis Comes.

Natale Conti or Latin Natalis Comes, also Natalis de Comitibus and French Noël le Comte (15201582), was an Italian mythographer, poet, humanist and historian. His major work ''Mythologiae'', ten books written in Latin, was first published in Venice in 1567 and became a standard source for classical mythology in later Renaissance Europe. It was reprinted in numerous editions; after 1583, these were appended with a treatise on the Muses by Geoffroi Linocier. By the end of the 17th century, his name was virtually synonymous with mythology: a French dictionary in defining the term ''mythologie'' noted that it was the subject written about by Natalis Comes.Conti believed that the ancient poets had meant for their presentations of myths to be read as allegory, and accordingly constructed intricate genealogical associations within which he found layers of meaning. Since Conti was convinced that the lost philosophy of Classical Antiquity could be recovered through understanding these allegories, "The most apocryphical and outlandish versions of classical and pseudo-classical tales," notes Ernst Gombrich, "are here displayed and commented upon as the ultimate esoteric wisdom."

Taking a Euhemeristic approach, Conti thought that the characters in myth were idealized human beings, and that the stories contained philosophical insights syncretized through the ages and veiled so that only "initiates" would grasp their true meaning. His interpretations were often shared by other Renaissance writers, notably by Francis Bacon in his long-overlooked ''De Sapientia Veterum'', 1609. In some cases, his interpretation might seem commonplace even in modern mythology: for Conti, the centaur represents "man's dual nature," both animal passions and higher intellectual faculties. Odysseus, for instance, becomes an Everyman whose wanderings represent a universal life cycle:

Despite or because of its eccentricities, the ''Mythologiae'' inspired the use of myth in various art forms. A second edition, printed in Venice in 1568 and dedicated to Charles IX, like the first edition, was popular in France, where it served as a source for the ''Ballet comique de la Reine'' (1581), part of wedding festivities at court. The ''Ballet'' was a musical drama with dancing set in an elaborate recreation of the island of Circe. The surviving text associated with the performance presents four allegorical expositions, based explicitly on Comes' work: physical or natural, moral, temporal, and logical or interpretive.

The allegorization of myth was criticized during the Romantic era; Benedetto Croce said that medieval and Renaissance literature and art presented only the "impoverished shell of myth." The 16th-century mythological manuals of Conti and others came to be regarded as pedantic and lacking aesthetic or intellectual coherence.

Nor were criticisms of Conti confined to later times: Joseph Scaliger, twenty years his junior, called him "an utterly useless man" and advised Setho Calvisio not to use him as a source.

Conti, whose family (according to his own statement) originated in Rome, was born in Milan. He described himself as "Venetian" because his working life was spent in Venice. Provided by Wikipedia

-

1by Conti, Natale, 1520-1580, Linocier, Geoffroy, XV./XVI.sec, Conti, Natale, 1520-1580

Published 1588

Call Number T 544 PABook -

2by Conti, Natale, 1520-1580, Linocier, Geoffroy, Giraldi, Giglio Gregorio 1479-1552Other Authors: “...Conti, Natale, 1520-1580...”

Published 1653

Call Number T 545 PA

Book -

3by Vergilius Maro, Publius 70-19 a.C, Erythraeus, Nikolaus 16. stor, Vegio, Maffeo 1406-1458Other Authors: “...Conti, Natale 1520-1580...”

Published 1596

Call Number T 86 PA

Book